Research

Embodied cognition is the theory that cognitive processes are fundamentally shaped by the body’s sensory and motor systems. It posits that thought and understanding arise through real-time, dynamic interactions between the brain, the body, and the environment, not from the brain alone. Embodied cognition challenges traditional views by proposing that our biological form and physical experience directly structure abstract thought and conceptual knowledge. We investigate this on macaques and human in naturalistic experimental paradigms in which the subjects freely interact with the environment and others.

For decades, the field of neuroscience has greatly benefited from conducting experiments in meticulously controlled environments. This is because the brain's interaction with the outside world is highly complex and the effect of one environmental variability is likely to be confounded by many others. Therefore, classically, neuroscientists probe the brain in repeated and carefully timed conditions, allowing a few variables at a time. Increasing the number of variables, one needs an exponentially higher amount of data to maintain the statistical power, a concept known as the curse of dimensionality. With recent advances in data-driven modeling and high-throughput computing, processing large amount of high-dimensional data in a reasonable time is feasible, allowing us to study decision making in naturalistic settings. Additionally, recording many channels of brain and body activity allows us to study neural correlates of ecologically valid behavior. As the animals' decision process continuously unfolds, we aim to understand the aspects of the decision making taking place, such as when the decision is made, where the animal is, and which option was chosen. We identify computational components in cortical areas that represent this process within the high-dimensional space of the activities of anatomical units, a.k.a. spiking neurons. Findings from this research will bring us closer to understanding successes and failures of decision making in real-life scenarios.

Computational models of naturalistic brain and body

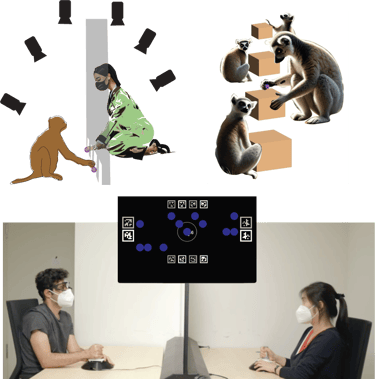

Surviving in the wild requires that primates stay aware of their surroundings while focusing on goal-directed activities. We aim to identify the state of vigilance, defined as the degree to which an individual seeks information from their surroundings in macaques and humans by monitoring their bodily and eye movements in controlled naturalistic environments. In macaques, we investigate how the natural states of vigilance influence foraging behavior and how they are represented in frontal and parietal cortical circuits. We employ a range of computational techniques to understand the richness and complexity of human and macaque behavior in similar scenarios while employing high-throughput electrophysiology to investigate the high-dimensional cortical activity. Findings from this project will help explain the representation of the inner state of vigilance in overt behavior and cortical activity and its potential influence on natural variability in goal-directed behavior.

Inferring hidden states of vigilance in macaques

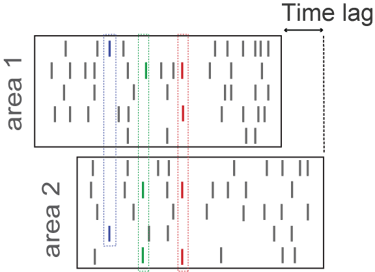

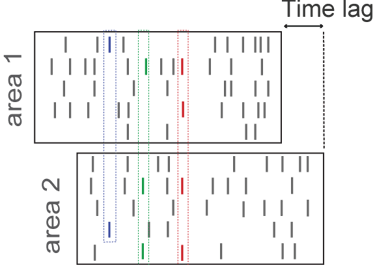

The role of cortico-cortical communication in cognition and perception

Complex decision making requires orchestrated activity across many brain areas that are representing the processing of external or internal information. Using state-of-the-art electrophysiological devices, we probe multiple brain areas simultaneously. We identify precisely timed coordinated activity across recorded areas to identify their role in making decisions.

Primates rely heavily on visual cues, such as gaze, head, and bodily expressions, to engage in social interactions and infer the intentions of others. This ability enables proactive decision-making in dynamic environments, allowing individuals to anticipate actions rather than simply react. Here, we seek to address key gaps in our understanding of the role of gaze-based communication in value-based decision-making in primates, specifically rhesus macaques, red-fronted Lemurs, and humans, using naturalistic, interactive scenarios. By studying macaques in controlled interactive settings, we will also investigate the roles of the parietal and prefrontal cortices in inferring and acting upon others' intentions. Experiments will involve tracking head, eye, and body movements during tasks where individuals must balance observing others’ gaze with competing demands of a behavioral task. Additionally, we will develop a predictive computational model using gated recurrent neural networks (GRUs) to analyze how gaze cues and social dynamics influence decision-making. This model will also serve as a tool to strengthen collaboration within UGaze, extending its application to other contexts, such as joint attention and gaze dynamics in human interactions. By bridging species and integrating advanced methodologies, we will contribute to UGaze’s goal of understanding the role of complex gaze patterns in social behavior.